Palantir: The Founder Foundry

Unpacking Palantir’s Founder Factory: Lessons in Talent, Mission, and Impact

Palantir has produced a remarkable number of founders and technology leaders: from founding startups like Anduril (Brian Schimpf, Trae Stephens, and Matt Grimm) and Affirm (Max Levchin and Nathan Gettings) to leading consequential organizations such as OpenAI (Bob McGrew - Chief Research Officer) and Fox (Melody Hildebrandt - CTO).

We wanted to dig into what makes Palantir special through the lens of company building and helping other founders apply best practices. A bit about us: Apoorv was a Forward Deployed Engineer at Palantir from 2013 to 2017 working primarily on the commercial side of the business (working with Palantir’s non-government customers). Cobi was at Palantir from 2014 to 2020 working predominantly on the US Government side of the business. Given our different functional and customer focus areas, we saw a broad spectrum of what makes Palantir special and below we distill some of the common elements that stand out.

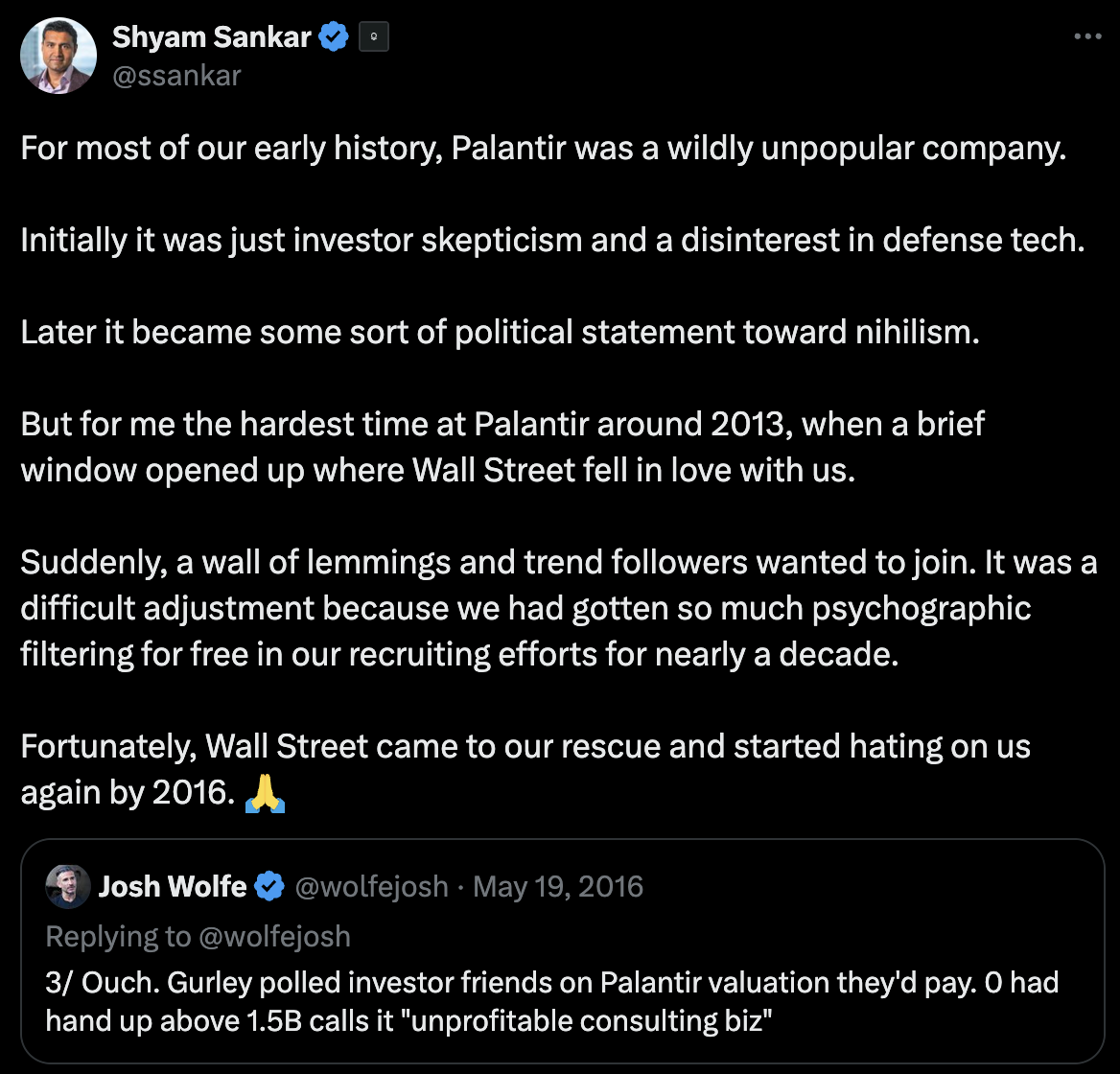

Palantir: a misunderstood company

Palantir has been -- and in many ways still is -- a misunderstood company. Over the years, Palantir has been called everything from a secretive spy organization that steals citizens’ data to a services business to a consulting shop.

Today however that tide has largely turned. The perception change has to do in part with defense tech becoming in vogue and with Palantir's strong public market performance (nearing $100b in market cap, and now a part of the S&P 500). While those are lagging indicators, the leading indicators lie in the special environment that Palantir creates and the associated training Palantirians receive.

Here are the key elements that create the magic of Palantir’s culture:

Uncompromising Talent Bar

Mission Orientation

Forward Deployed Engineering: Deliver Outcomes, Not Software

Seek Truth: Solve Real Problems, Not Shiny Ones

Define a Shared Enemy: United The Team

Flat Structure: Direct Access To Leadership

Radical Transparency: Learn From Everything

#1 Uncompromising Talent Bar

Palantir maintains a high bar for talent. For as long as we were there, every candidate was interviewed by one of the founders (typically Alex Karp or Stephen Cohen) as their final interview. This created a tax on the organization given the founders' schedules were limited, but it also kept the bar incredibly high. Palantir screens for people with T-shaped skills—deep in certain fields while being able to collaborate across disciplines with experts in other areas. Palantir CTO Shyam Sankar writes:

“When forming a team, I don't want to assemble a polite roster of cross-functional professionals. I want the X-Men: a medley of mutants united for good.”

One piece of training Palantir prescribed to interviewers was to always ask ourselves: “What would make us think the opposite of what we currently think about a candidate?” If a candidate was doing really well in the interviews, we’d design their next set of interviews to see what would make us change our decision to not hire. Similarly, for candidates with sharp T-shaped skills but who were struggling in the process, we’d also ask the counterfactual: what could the candidate demonstrate to change our minds and receive an offer?

Finally, retention of your strong performers matters. One of the hardest parts about having a talented pool of employees is that it’s hard to keep them together. Humans go through phases and so do companies. As Palantir’s Head of Commercial, Ted Mabrey, describes it:

“(At) Palantir, a person would have to stay committed through phases that included: products that were closer to pipedreams than viable for years, raising hyped private rounds as a sexy unicorn, being the most maligned company in the valley with literal protesters at your door, having your options underwater, a life-changing event in going public, an ~80% drop in stock price, and deciding to climb those mountains all over again with yet a new platform.”

But Palantir did an exceptional job of keeping this group together, in large part driven by the strong mission orientation.

Apoorv at a Palantir recruiting booth on a college campus

#2 Mission Orientation

In our first weeks at Palantir, we quickly learned that sleep is overrated and coffee is underrated. Shyam covers it well in his post "The Case Against Work-Life Balance: Owning Your Future" as to why working 70+ hour weeks was not heroic, it was standard. Palantir consistently outworked its competitors, but the reason behind this relentless drive was far more compelling.

Palantir employees were driven by a sense of purpose far beyond monetary rewards. The mission was everything—it became a personal, deeply ingrained commitment to achieve a shared goal that was larger than each of our individual existence.

Teams were deeply mission-aligned, with every project outcome evaluated as either a WIN or LOSS. That is an incredibly powerful way to fuel your fire! This culture of winning was ingrained and our team operated with singular focus on achieving mission success. Shyam summarizes it well in “The Primacy of Winning”. Drawing from its roots in defense technology, Palantir extended this mission-driven mindset beyond defense and into commercial applications. Even commercial teams were structured like military units, with Commanding Officers (COs) leading Forward Deployed Engineers (FDEs) referred to as Deltas and less technical forward deployed individuals known as Echoes.

Setting the mission to be larger than one’s own identity is a winning formula. Teams who are able to rally around that shared mission are in possession of a superpower. Some teams we see that have a similar level of alignment towards a shared goal are SpaceX (mission: making humanity multiplanetary), OpenAI (mission: developing AGI to benefit humanity), and Anduril (mission: equip US and allies with defense tech to secure sovereignty).

#3 Forward Deployed Engineering: Deliver Outcomes, Not Software

Palantir pioneered a new breed of engineer—FDEs—who didn't just deliver software, they delivered outcomes. These were engineers embedded directly with customers to solve on-the-ground challenges, ensuring the tech created real-world value, no matter the complexity.

When delivering tangible value is the mission, FDEs don’t stop at delivering software. They go above and beyond to build the supporting ecosystem. This often includes the less glamorous “plumbing” work, like data integrations, or solving non-technical challenges like incentive alignment within an organization (e.g., what if Palantir’s implementation causes certain jobs to become redundant?). Operating as an FDE is rarely glamorous, but it is arguably the most critical role for ensuring success. The focus is on results, not just technology.

You may wonder: isn’t it incredibly expensive to serve customers with these FDEs? The answer is yes, but Palantir’s median Annual Contract Value (ACV) is $5 million. When a customer is paying that much, they are not just purchasing technology; they are purchasing outcomes, and FDEs are the ones ensuring those outcomes are delivered.

Source: Meritech Comps

The need for such a role is not unique to Palantir. The same pattern is evident in today’s AI landscape. As with any new technology, the existing tech stack is often not mature enough for something like generative AI (today) or Spark (a decade ago) to “just work” and deliver value. FDEs make these new technologies viable and ensure they deliver results, which is why their skillset is highly sought after today.

FDEs have come a long way—from being criticized as mere “consultants” to being revered as the frontline “AI engineers.”

#4 Seek Truth: Solve Real Problems, Not Shiny Ones

A core principle at Palantir—especially among FDEs—was the relentless pursuit of solving real user pain points, not just shiny problems. This often required 'tasting the soup' by spending time with users in their environment—whether that was down the street or on the other side of the globe.

For instance, in our work with the military, we had servers deployed on ships. We didn’t initially consider how the physical rocking of ships at sea would affect these servers—like becoming unplugged—which had implications for caching frequency, downtime procedures, and a host of other technical and process issues. If we hadn’t been physically present, we wouldn’t have known to solve these problems. The challenges weren’t always strictly software.

Similarly, at a forward operating base in the Middle East, the military unit had to take inventory of every hard drive on every server each week. This meant physically pulling out hard drives from servers we had installed. We had to develop clear shutdown procedures and a reinstallation sequence to make this possible without interrupting operations.

Our work often meant solving less glamorous, yet crucial, issues, like cleaning data or building software to make data easier to use. It wasn’t always the sexiest or hardest technical challenge, but it was often the most critical to achieving user outcomes.

Cobi on a military base training US Marines

#5 Define a Shared Enemy: Unite The Team

One key cultural element at Palantir was defining a shared enemy. Mandatory reading included "The Looming Tower" by Lawrence Wright, which highlighted the importance of understanding your adversary. Every team, including those not focused on government work, managed to define their own shared enemy.

For government projects, the shared enemy was often the customer itself—the government—with all of its inefficiencies and bureaucracy. In commercial projects, the enemy sometimes was consulting giants like BCG or McKinsey, and other times it was the drudgery of spreadsheets and siloed information.

Palantir took on entrenched bureaucracies so seriously that they even sued the U.S. Army to overcome procurement roadblocks—and won. This was in the spirit of overcoming inefficiencies, similar to SpaceX’s lawsuit years before.

In one instance, we were working with a civilian US Government agency, competing with Booz Allen Hamilton for a large contract. It wasn’t a question whether Palantir’s offering or Booz Allen’s cadre of dashboard makers was a better choice - Palantir delivered better performance at a better price point. It was a question of justice -- would the Government choose the right answer (Palantir) over the legacy approach (Booz). Using the shared enemy of ‘large government contractors trying to solve foundational data challenges with flimsy dashboards’ allowed our team to rally together to work exceedingly hard for this agency.

With the combination of mission orientation and a shared enemy, we were motivated to try to solve any problem. This shared enemy was also valuable for long term orientation and motivation -- taking down the largest evils in the world takes time and can’t be accomplished overnight. To beat Raytheon or Booz Allen -- or to beat technological ineptitude out of the US Government -- takes consistent, durable work.

Cobi at a DHS deployment in support of a National Special Security Event

#6 Flat Structure: Direct Access To Leadership

Palantir tried to maintain a flat organizational structure. Alex Karp and Shyam Sankar often reached out directly to individual contributors, cutting through layers of management and delivering “Gamma radiation”. Shyam writes:

“Mentorship is likewise critical when directing mutant powers towards the greatest possible good. The X-Men would not have become X-Men without Professor X’s School for Gifted Youngsters. But again, the standard model doesn't apply. To begin with, you need mutants to mentor mutants, and in many cases, to provide the initial dose of radiation. Otherwise, even the best institution of higher learning will predictably devolve into a lemming academy. Once mutation is in process, one of the greatest aspects of mentorship is, paradoxically, autonomy. This is especially important because extreme growth doesn't happen on schedule, but is subject to periods of intense activity. As a mentor of mutants, you need to be attuned to these periods, and when they come, confer even more autonomy. Above all, fight your instinct to handhold (hard to do when both hands are always clenched in a fist anyway!)”

This "gamma radiation" approach—similar to the leadership styles of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos—allowed direct communication and rapid decision-making. It also had a side effect of providing great opportunities to everyone in the company to learn.

#7 Radical Transparency: Learn From Everything

Radical transparency at Palantir wasn't just a practice—it was foundational for building alignment across the company. Every email, decision, and retrospective analysis was available to all in the company, breaking down silos and creating a hive mind that thrived on collective learning

Several practices exemplified this transparency:

Almost all emails were accessible to everyone in the company.

Meeting reports were written and shared with the entire company after every important meeting.

When something didn’t go according to plan, retrospective analyses (e.g., the Five Whys) were documented and made available in the internal company wiki for all teams to learn from.

Most team wikis and notes were open for others to access, breaking down silos and encouraging cross-team learning.

This transparency helped Palantir quickly gather and spread lessons across teams, ensuring that everyone learned from each other's experiences and drove collective outcomes.

Palantir’s True Legacy

Palantir’s true legacy isn’t just its software or contracts—it’s the people it has trained and launched into the world. The leaders, engineers and founders that have emerged from Palantir carry with them a relentless focus on mission, a commitment to delivering results, and the ability to lead teams in tackling big, audacious challenges.

For any company or startup, the lessons from Palantir are clear: Set an uncompromising talent bar, rally around a shared mission, and always seek to solve real problems.

Thanks to Cobi Blumenfeld-Gantz, Sud Bhatija and Shreya Bhargava for their inputs on this article.

Interesting read. What are your thoughts on their Meritocracy Fellowship?

Didn’t know Shyam before. Exploring him right now.